|

Three articles from this weekend’s New York Times deliver a gut punch to anyone still wondering whether they should hand their kids an iPad to keep them quiet at a restaurant. The answer, you might have guessed, is “no way.” At least, that’s the loud, clear message from the people who designed and built the screen you’re reading this blog post on right now. How do tech executives describe the products they and their employers have foisted upon humanity? “Crack cocaine…going straight to the pleasure centers of the developing brain,” says one. “I am convinced the devil lives in our phones and is wreaking havoc on our children,” says another.

Silicon Valley isn’t known as a bastion of social conservatism. When tech elites liken their own products to hardcore drugs and Satan, it's probably not to throw down a culture war gauntlet. More likely, these folks know something horrible is happening, especially to kids, and they want to stop it. Alarm grows outside of Silicon Valley, too. A Kansas City pediatrician interviewed by the Times calls screens a massive “social experiment” using poor and middle-class children as test subjects. A British Member of Parliament this week published an op-ed in which he compared parents’ and children’s screen use as a creeping crisis "akin to climate change." Half a world away, Chinese health authorities recently released nationwide guidelines for diagnosing and treating adolescent internet addiction. Why the warning bells? Perhaps it’s because we’re reaching a global tipping point of awareness of just how drastically some fundamental human behaviors and health factors appear to have changed since the advent of ever-present screens. As screen use has risen, rates of sexual intimacy and procreation have declined. As online porn consumption and availability has risen, so have rates of young men reporting problems with erectile dysfunction and of young adults struggling with intimacy. As social media use has risen, teen mental health has declined. Screen use has been linked by researchers to sleep disruptions, declining person-to-person interaction, and a plethora of unwanted addictions and compulsive behaviors. Researchers rightly point out that correlation is not necessarily an indicator of causation. Long term studies, not anecdotes, are necessary to establish scientific conclusions. Screens, in the form we use them today, simply haven’t been around long enough for multi-generational longitudinal study. And yet, we’re not blind to screens’ effects on our lives. It’s not just that people are getting into horrific car wrecks because they feel the insatiable need to send a text at 65 miles per hour. It’s not just that “phubbing” (snubbing people by staring a phone) is actually a thing. It’s not just that people are becoming more sexually responsive to cold pixels than to a warm touch. It’s not just that research has coined a term (“ludic loop”) to describe the trance-like state video gambling (and other screen) addicts enter when they stare at a screen for hours on end, or that screen content designers readily admit they aim to manipulate and exploit their users’ primal psychological responses to help them enter that state. It’s all of those threads woven together that make it feel like screen use has us trapped in a terrifying spider’s web. Traffic to PornHelp.org has grown steadily since our founding in February 2016. As our readers know, we’re based in the U.S. But, our visitors come from all over the planet these days. That global interest in our mission is, to us, the strongest signal that Silicon Valley executives have good reason to keep their own children as far away from screens as possible. Screens bring the same problems wherever they go. A college student in India reports the same life disruptions from using online porn as does one from Brazil, or France, or Kansas. Chinese teens and British teens struggle equally with compulsive gaming. Humans everywhere, no matter their age, gender, race, religion, ethnicity, or culture, seem equally attracted, entranced, and disturbed by screens. So, consider this a wake up call. Around the world, alarms are ringing. Red lights are flashing. For all the productivity and creativity screens bring humanity, they also inflict widespread and indiscriminate harm. Like so many Dr. Frankensteins, tech designers show growing terror at what their creations have wrought. These people? They know. Something horrible is happening.

0 Comments

A while back, we wrote about the unfortunate politicization of the porn addiction “debate,” such as it is. We return to that theme this week in light of the sad display of political polarization Americans are witnessing in the ongoing Supreme Court nomination battle. As our readers know, we don’t express political views here. But you don’t need to take a side to recognize how the Great Kavanaugh Blowup has reinforced the ugly political and social rifts in this country.

It makes us wonder, what is going to heal the wounds we keep inflicting on our country? It seems like, every time we start to knit things back together, something or someone goes and picks at a scab, and the bleeding starts all over again. So, here’s our modest proposal for a place to start. Porn! That’s right, porn. Or, more precisely, internet porn use and screen-based addictions generally. How is turning our national attention to problematic online porn/internet/screen use going to heal the country? Let’s break it down. Reason #1: The Right Wants to Tackle This Issue. Nothing warms the heart of conservative America more than bemoaning the world going to hell-in-a-hand-basket because of naked bodies and “kids today.” It’s a time-honored tradition. Pastors have Bible verses and jazzed up hymns at the ready. Little old ladies can’t wait to wag their fingers at the first sign of cultural decay and encroachment by liberal, coastal elites. Folks really, really, really want to make America great again. And, what better place to start than tackling the one thing that indisputably didn’t exist back in those halcyon days? Kids today hole up in their bedrooms with laptops and phones, disappearing into a fog of porn or Fortnight or Instagram (or all three) for hours and hours and hours on end. It's a conservative's feast: clear evidence the next generation is doomed! Reason #1A: The Left Wants to Tackle This Issue Too. It’s not just conservatives who are geared up to address how out-of-control screen time erodes our families, minds, and societal norms. Here’s a quiz: can you guess the one group of Americans most firmly committed to keeping their kids away from screens? Nope, it’s not Heartland dwellers. It’s Silicon Valley executives and engineers! No joke. The world’s most Waldorf-school-loving, social-justice-warring, non-vegan-shaming, gender-neutral-bathroom-building liberals uniformly agree on one thing: the screens they want you to buy stuff on, play games on, read gossip on, and surf porn on, are bad for their own children. They won’t let their kiddos near an iPad…and they're the ones who make iPads. Oh, and you know who else thinks screen time is bad for kids? The French!!! Seriously now. How much more liberal can you get? Reasons #2 through Infinity: Everyone Wants to Tackle This Issue Because it Involves Our Kids. Yeah, we’re being a little tongue-in-cheek. But, look, if there’s something we all want no matter our political affiliations, it’s for our children to grow up safe. Parents everywhere understandably worry about every new trend and technology children seize on, especially when we still haven’t caught up to whatever it was they were into six months ago. Sure, sometimes we might blow the dangers out of proportion, but it’s not wrong to worry. That’s what parents do. The thing is, sometimes it’s not only natural to worry, it’s also correct. And, when it comes to online porn/social media/gaming, there’s real cause for concern. Our focus on this blog is porn, so we’ll start there. Yes, humans like looking at naked bodies. No, doing that in moderation isn’t going to kill anyone. But, when normal adolescent sexual curiosity meets streaming hardcore pornography, available 24/7/365 in unlimited quantities for free, it’s not hard to see how things can go off the rails. The purveyors of online porn engineer it to attract and hold users’ attention, and train their AI to keep users engaged by showing them ever-more novel content specifically tuned to past porn use patterns. Make no mistake: online porn platforms know exactly what your teenager watches, and when he or she watches it, and for how long, and what type of content and rewards will keep him or her on the site longer next time. That’s not paranoia on our part. It’s an indisputable fact. The result: a gigantic experiment in mind-control and sexual conditioning of young people who, by dint of their age alone, haven’t reached a stage of maturity that allows them to discern among, digest, or cope with often violent, exploitative, and outlandish depictions of sexual activity; an experiment which may, for some, devolve into a compulsive obsession that proves ruinous. These dangers also extend to other forms of screen-based content. Social media companies engineer their product to capture and hold attention, and to engage those parts of the adolescent brain most susceptible to wanting, needing, “likes” and emoji and social acceptance. Games, too, whether focused on fighting, sports, or skill, also engage users by rewarding compulsive, prolonged use, teasing the promise of achievement and bragging rights. Let’s be clear here. We’re not saying that sexual curiosity, a desire for social validation, or wanting to play games with one’s friends are inherently bad for kids. Our concern is that the means by which the world’s children and adolescents are being conditioned, one might even say forced, to indulge these impulses have been rigged against their long-term wellbeing in order to increase profits for porn, app, and game developers. We worry about how screen-based content amplifies, distorts, and exploits “normal” child and adolescent behavior without any regard for the entirely predictable negative outcomes. It’s a real problem. It’s also one that folks from the right, left, and center have reasonable approaches to addressing. When it comes to porn, for instance, age verification has the potential to play a significant role, as it has in the UK. So, too, does investing in education about human sexuality, intimate relationships, respect, consent, and being a wary consumer of anything delivered for “free” on-screen. There’s room for dialogue, compromise, and mutual respect and understanding on these solutions, because we all see an obvious need to protect our children. So, on what promises to be another contentious, polarizing day in American history, let’s embrace an issue that brings us back together. All reasonable, conscientious Americans, no matter their politics, can unite behind addressing the impacts of porn/screen use and addiction on our children. There's no better time to start than the present. Agreed?

This post is the third in a series in which we explore the “Salience Value” (SV) of online porn. SV is the term we’ve coined for a notional measure of online porn’s ability to attract and hold a user’s attention.

We proposed in two previous posts that SV can serve as a rough predictor of whether a user falls into problematic patterns of porn use, and that SV comprises two distinct elements based on concepts used by neuroscience researchers: “perceptual salience” (how well the design and presentation of porn attracts and holds user attention) and “acquired salience” (how a user’s personal valuation of the porn use experience causes porn to attract and hold user attention). In this post, we draw from those previous exercises and take a look at how to reduce or mitigate the SV of internet porn. Our aim here is not to make qualitative judgments about how effective these interventions might be in reducing porn use. Instead, our goal is simply to organize into coherent categories for further discussion the different modes of reducing/mitigating porn's SV. The two concepts of salience we covered in our last post, “perceptual” and “acquired,” suggest two generalized, but distinct, approaches to the problem of reducing/mitigating SV. On one hand, if we want to make a dent in the “perceptual salience” of porn, we need to make changes to how the user is able to perceive it. On the other hand, if we want to reduce the “acquired salience” of porn, we need to make changes to how the user values the experience of that perception. We don’t think it would be accurate to treat these concepts as independent of each other. Changes to perceptible features of porn can affect how the user values it, and vice versa. Still, for simplicity’s sake, we think it’s useful for starters to locate interventions that could reduce/mitigate the SV of online porn along a spectrum, with “perceptual salience” at one end, and “acquired salience” at the other: PS <———————————————————————>AS (changes to how porn (changes to how user can be perceived) values porn) Using that spectrum as a rough guide allows us to organize interventions for reducing/mitigating the SV of porn into four general categories: Category 1: Pure Perceptual Salience Interventions One way to reduce/mitigate the SV of online porn is to alter the porn itself. By this we mean making porn less attractive to the five senses, such as by altering its: - color; - sound/volume; - screen size; - screen resolution; - auto play/preview; - continuous play; and - content duration. Some of the most popular life hacks in the porn-quitting community fit into this category, such as changing screens from color to grayscale and turning off continuous and auto-play features on streaming video sites. Category 2: Mostly Perceptual Salience/Slightly Acquired Salience Interventions This next category deals with altering the means of interacting with online porn to reduce/mitigate its SV. We categorize these interventions as mostly relating to changing “perceptual salience,” but also affecting “acquired salience,” in that the user’s interaction with a porn platform can both change how the user is able to perceive the porn and how the user values the experience of perceiving that porn. These interventions might include changes to: - user’s ability to control the presentation of content; - user’s ability to choose which content to consume; - depriving a user of sensory inputs; and - limiting the user’s time available to consume content. For instance, if a user lost the ability to scroll through content, to adjust the volume, to choose what types of porn he sees, or even to have a tactile interaction with his screen, these interventions could reduce the porn’s SV for the user mostly by negatively altering what the user sees on screen, but also by causing the user to value the experience less. Category 3: Mostly Acquired Salience/Slightly Perceptual Salience Interventions Traveling further along the spectrum, we come to interventions that alter the user’s valuation of his porn use experience via external influences. These interventions work mostly upon the user’s subjective enjoyment of using porn, but also may have a direct impact on the user’s ability to perceive porn at all. Generically speaking, we’d classify these as “social” interventions of one form or another that interfere with the user’s desire for anonymity and privacy. They may include: - publicizing the porn use; - observing the user during porn use; and - subjecting the user to accountability for porn use. Accountability software, putting a home computer in a “public” part of the house, and deterring use through threatened negative consequences/punishment all fall into this category. Category 4: Pure Acquired Salience Interventions Finally, some interventions that reduce/mitigate the SV of online porn work purely at the level of changing the user’s valuation of the experience of porn consumption through internal influences. These interventions assume nothing about the porn or the user’s means of interaction changes, but instead the change occurs for the user from the inside-out. They may include: - therapy; - mindfulness; - medication; - non-medication health improvements (diet/exercise/etc.); - education about porn leading to aversion; and - applying religious/moral principles leading to aversion. These interventions have the potential to cause a user to place a lower value on the experience of using porn, and therefore to react to it more negatively. You may have noticed we’ve skipped one obvious intervention, which is cutting the user off from porn altogether through content filtering, elimination of screens/going “low tech,” age verification, paywalls, etc. We’ve excluded these interventions up to now because they don’t fit neatly on a spectrum of interventions, but rather, represent both a pure “perceptual salience” intervention and a pure “acquired salience” intervention. Eliminating access to porn makes perceiving it and valuing the experience of using it impossible. Consequently, we can place that intervention on both ends of the spectrum, or conceive of the spectrum as bending until its ends meet and it forms a circle. As we said at the outset, we’re not prepared at this point to judge the effectiveness of any of these approaches to mitigating the SV of porn. We suspect different interventions, and combinations of interventions, work for different people. We’ve heard some people in recovery from porn addiction say “I still love porn but I know I can’t be near it.” We’ve heard others say “now that I know what porn is does to me, it disgusts me.” Some find relief from using porn in being found out. Others in recognizing and addressing the feelings they associate with an urge to binge. For the same reasons, we cannot say which, if any, of these interventions may do more harm than good for a particular user. It's possible the intervention that helps one user could cause another user greater degrees of emotional distress than the porn use itself. We can't evaluate that here. For now, our hope for this post is simply to contribute to the ongoing discussion of how sufferers, researchers, advocates, and treatment providers can organize their thoughts about ways to quit porn and tackle compulsive porn use. We believe the more systematic and uniform our community can make the process of selecting interventions to reduce/mitigate the Salience Value of porn, the more precise and effective those interventions can eventually be. As always, comments welcome.

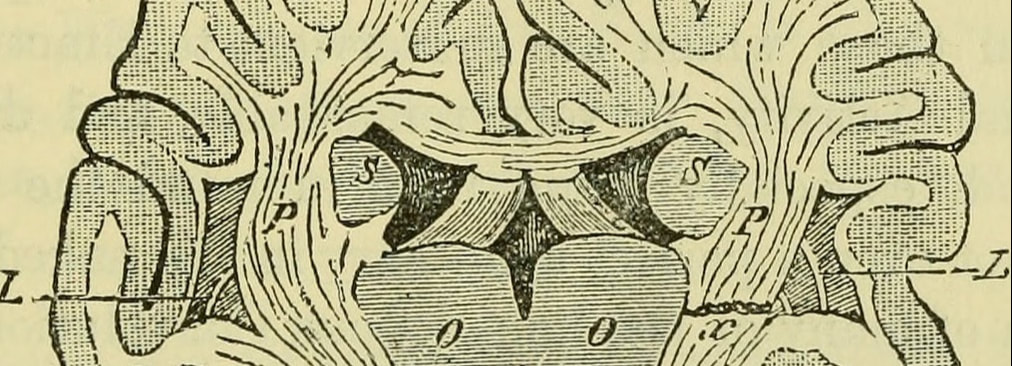

In a previous blog post, we argued the “Salience Value” of screen-based content could serve as a predictor of whether a screen user would fall into a “ludic loop” of problematic content consumption. In this post, we delve deeper into the concept of salience and how it may influence porn use and other screen content consumption behavior.

In their 2017 treatise Decision Neuroscience, researchers Kahnt and Tobler wrote: “At the most general level, salience can be defined as the capacity of a stimulus to direct attention.” They went on to describe, however, some confusion in the neuroscience literature between two concepts for which the term “salience” has been used as a shorthand. One of those concepts, “perceptual salience,” refers to “physical properties (i.e., the color, contrast, orientation, or luminance) that make [a stimulus] more likely to capture attention.” The other, “acquired salience,” refers to “the importance that a stimulus has acquired through association with an incentive outcome.” (It bears noting that both “perceptual” and “acquired” salience may have alternate definitions outside of the neuroscience context, amplifying the definitional ambiguity.) In our blog post proposing a model for “ludic loops,” we posited (based mostly on anecdotal evidence) that screen-based stimuli – porn, social media, gaming, etc. – have a measurable Salience Value (SV), and that SV has a direct correlation to the likelihood of a problematic “ludic loop” use pattern arising. We hypothesized that the SV of screen-based content features at least two core components: (1) how the content is designed to attract attention, and (2) how the content responds to the user’s deep-seated or primordial needs. These two categories roughly correspond to the concepts of “salience” in neuroscience research articulated by Kahnt and Tobler. Screen content can be engineered to increase its “perceptual salience,” and can feature subject matter that varies in its “acquired salience” according to its fundamental importance to the user. Delving into those distinctions further, consider how the design engineering of screen-based porn (or social media or gaming) increases “perceptual salience”. Over the past year, ex-Silicon Valley engineers, among them former Google design ethicist Tristan Harris, have warned about the tricks and techniques app and web designers use to grab and hold the attention of content consumers. These include on-screen content placement and visual design, leveraging unpredictable rewards, auto-playing video content, infinite scrolling, and tracking user movements to design even more enticing, personalized future interactions. You don’t have to be a neuroscientist to recognize how effective these design features can be. Hands up if you’ve ever lost time scrolling through Instagram or playing Candy Crush. We can’t see you, but we know you have your hand up because we do, too. Similarly, consider how degrees of “acquired salience” impact a user’s interaction with screen-based content. In our previous blog post, we contrasted the SV of porn with that of cute cat videos. Both may appear on screen in an identical, YouTube-style interface. Both likely feature design engineering calculated to grab and hold user attention. But, only one speaks to a primordial need – the sex drive – of most users. Kahnt and Tobler describe “acquired salience” as relating to the importance of a stimulus for motivated behavior independent” of whether its outcome is positive or negative for the content consumer. That makes sense in our model, because sexual content, whether it arouses or disgusts, holds an “absolute” value for most people that is far greater than more neutral content that rarely arouses or disgusts, such as cat videos. Kahnt and Tobler also observe that “acquired salience” may vary according to learned expectations about the outcome tied to the stimulus. In the context of screen-based content, does this imply “acquired salience” can vary over time? Anecdotally, we suspect so. We think the “acquired salience” of a cute cat video be high initially (when a consumer finds himself entranced by the hilarity of watching a cat fall from a piano bench), but can decline predictably as the novelty of cat antics decreases. Conversely, the “acquired salience” of online porn sustains (or even grows) in intensity because of the near-infinite variety of pornographic genres, themes, and on-screen behaviors available for consumption. Simply put, online porn doesn’t just tickle a particularly potent human instinct, it also remains salient by offering the opportunity to discover new outcomes, no matter whether they are positive (arousing) or negative (disgusting). Summarizing and simplifying these concepts, here’s the state of our thinking at this point on the Salience Value of screen-based content, particularly online porn. From the perspective of the user, the SV of screen-based content depends upon both exogenous (originating externally) and endogenous (originating internally) factors. Those factors aren’t necessarily held constant. In fact, they’re likely highly dynamic. Engineers can tweak exogenous factors to make content more perceptually salient, and users can respond by adapting modes of use that mitigate those tweaks (e.g., by going gray-screen). Likewise, users’ endogenous valuation of subject matter can evolve through learning, experience, aging, and (perhaps) medical interventions, but can be countered by content providers when they produce ever-more novel subject matter. Why bother with this exercise? As we wrote previously, we think there's a need to spur focused discussion about the multiple variables that may contribute to problematic online porn use and other compulsive, screen-based behavior. Too many discussions of porn addiction we read proclaim the problem too difficult and nuanced for effective analysis. Our fondness for behavioral economics leads us to believe that basic modeling and multi-disciplinary analysis can bring order to chaotic discussions like these, and perhaps lead to treatment methods tailored to each problem user's needs. Comments welcome.

We were recently invited to sit in on a high school class that asked students, over the course of a semester, to envision how they wanted their own lives to unfold in the coming decades. As the guests of honor, we were there to field questions from the students – all high school seniors – about what we’d learned since we left the cocoon of secondary education.

No softballs came our way in this class. These kids had already been thinking about their questions for a few weeks under the guidance of their teacher, and quickly honed in on some core life issues: “Are you happy, however you understand that word?” “Do you think of yourself as a good person, and are you?” “What’s the biggest mistake you’ve made so far?” And, “If you were going to write a letter to yourself at our age, what advice would you give?” We won’t lie, the session got pretty raw. Not so raw as to tell an unsuspecting group of teens what it’s like to be in recovery from porn addiction, mind you. It wasn’t that kind of setting. But still, we’d lay odds these kids had never heard a group of adults in their 30s and 40s open up about vulnerabilities in way yours truly and others did. One adult talked about coming late to the realization of how important it was to fail miserably. Others reflected, sometimes tearily, about how dreams of having children or careers had eluded them. Perhaps the most trenchant question, for your correspondent at least, was the last one – what advice would you give to the high school senior version of yourself? Now, remember, these students had already done a lot of thinking about this topic. By the time that question surfaced, we were way past answering in clichés like “don’t take yourself too seriously.” In contemplating a response to that question, our inner monologue went something like: “I’D TELL MY 18-YEAR OLD SELF TO QUIT LOOKING AT PORN!!!!” But, raw as the class was, getting into the nitty-gritty of porn addiction seemed too specific. The students were asking the adults to translate our experiences into lessons that would be universal, not idiosyncratic. The adults stepped up the challenge with some uniformly insightful answers:

We have no idea which, if any, of the other adults in that class was in recovery. Their answers, however, struck us as something of a textbook lesson in emerging from addiction, and in turn, of how addiction recovery distills and seeks to address the core challenges of human existence. Would our 18-year old selves have listened to that sage advice? The premise of the class, at least, was we would have. Which is why we feel lucky to have spoken to those young adults. We may not be able to turn back time on our own addictions, but we can play a part in shaping how others confront the future, and in so doing, in making the world a healthier place.

As readers of this blog know, PornHelp.org neither endorses nor rejects any religious practice or principle. What follows is intended as a reflection on a concept in Judaism that may resonate for anyone – religious or not – in recovery from porn addiction. We trust our readers will not mistake this, or any of our writings for that matter, as an attempt to proselytize or pass judgment on anyone’s religion or non-religion. This is merely a perspective we find interesting and think you might too.

Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement in the Jewish religious calendar, begins this evening. In synagogues around the world, congregations will hear the Hebrew word teshuva spoken. Dictionaries translate teshuva (sometimes spelled t'shuva) as “repentance” or “return,” but those words fail to capture the breadth of the concept. In his 2010 book Repentance, author and professor emeritus of religious studies at Carleton College Dr. Louis E. Newman explores how teshuva pairs two essential perspectives on atoning for wrongs, one backward-looking, the other forward-looking. To “repent” in the sense of teshuva is not simply to take responsibility for past behavior by apologizing and feeling remorse. Repentance also must encompass future actions taken in the belief that renewal and grace are possible. As Dr. Newman pictures it, teshuva stands for a person “returning” to their “whole” being - owning and making amends for the past, but also turning toward a future in which the past does not limit one’s goodness and potential to contribute to the world. Addiction, whether to porn, pills, gambling, or something else, leads people into lives of shame, isolation, and self-hatred. Every binge and bender only compounds feelings of worthlessness and despair, in turn accelerating the addictive spiral. People suffering from addiction often implode, even die, when this cycle overwhelms them. The concept of teshuva described by Dr. Newman might be useful in braking addiction's destructive acceleration. In our experience, in the struggle with addiction, we often overlook the inherently positive corollaries to even the most negative of our emotions. We feel shame because we try, but fail, to curb the compulsive behavior ruining our lives. We feel despair because we believe recovery should be possible but can’t see the way forward. We isolate ourselves because know we’re not the people we worry others might see us as if we reveal our addiction to them. In other words, to borrow from Dr. Newman’s conceptualization of teshuva, as human beings we have the innate capacity not only to understand and express remorse for how our addiction hurts ourselves and others, but also to believe in and commit ourselves to a course of action in which our true self emerges from the shadow our addiction once cast. You don’t need to be religious to appreciate the power of this conceptualization of human potential when it comes to recovering from addiction. Dr. Newman, who himself has been in recovery, observes that “Our lives are marked not by our achievements, or certainly not by them alone, but rather by how we deal with our failures….” By embracing our failures in addiction as ruptures deserving of our sincere remorse but also capable of repair through our future action, and then taking that action, we lay the foundation of our recovery. Or, as Dr. Newman puts it, by being both retrospective in our regret and prospective in our hope, we allow ourselves to “return” (in the sense of teshuva) to being the people we have always wanted and tried (however unsuccessfully in the past) to be.

Here at PornHelp, we know the frustration of trying to explain a porn binge to those who haven’t struggled with addiction. No esoteric explanation we’ve tried (“trapped in a bubble” “falling into a deep hole”) ever succeeds in describing that simultaneously intense, detached, and hellish experience.

Which is why our ears perked up when we first heard the term “ludic loop.” That’s the phrase coined by NYU professor and researcher Natasha Dow Schüll to describe the trance-like state video slot machine users enter for hours on end while their money ticks away on losing bets. In a recent interview with Medium, Dr. Dow Schüll described a “ludic loop” as the experience of being “hooked into doing something that has no real reward, and the feeling of being trapped in that state of empty limbo becomes the reward in and of itself.” Or, as one of Dr. Dow Schüll’s interviewees for her 2015 book examining the rise of video slot machines, Addiction by Design, put it: It’s like being in the eye of a storm … Your vision is clear on the machine in front of you but the whole world is spinning around you, and you can’t really hear anything. You aren’t really there – you’re with the machine and that’s all you’re with. Sound familiar? It sure does to us. Specifically, it sounds like what happens when a person struggling with porn addiction sits down with his laptop at bedtime and heads over to PornTube, and the next thing he knows it’s 4 a.m. It also sounds like what happens when you scroll through an Instagram feed for an hour without stopping, or when you fire up a gaming app during your morning commute and miss your stop by miles. Our brain’s ability to enter a trance state is not necessarily problematic in-and-of-itself. In the Medium interview, Dr. Dow Schüll observes ludic loops can occur when you drive a car: you stay functional but achieve a pleasant, zoned out state at the same time. Dr. Dow Schüll describes this state as mildly problematic if you do nothing but drive in circles to achieve a blissful, detached high. But, as anyone who’s ever taken a long road trip knows, that same trance state occurs even when you do have a destination. Do you remember every stretch of the 100 miles you just drove? Of course not. That’s because we humans have an innate capacity to dial-in and tune-out simultaneously while performing complex, goal-oriented functions. It’s a useful evolutionary adaptation, really. Behind the wheel, you feel detached and protected from the unpleasant boredom of driving long distance, but you also flawlessly execute the relatively complex tasks of monitoring your speed, changing lanes, keeping track of other drivers, and avoiding hazards to arrive at your destination. Hunters describe a similar experience while tracking their quarry. Researchers refer to this as a “flow state”. Athletes often call it “the zone.” Whatever you call it, our ability to focus and detach all at once can help us achieve seemingly super-human ends. But what if you arrive at your destination and you don’t want to stop? Or you feel you’d rather just stalk a deer forever instead of pulling the trigger? Dr. Dow Schüll’s theory, paraphrased, is that when the bliss of the “zone” feels better than achieving the goal, you end up stuck in the zone’s evil cousin, a “ludic loop.” Of course, most people don’t drive in circles forever, stalk deer forever, or (to borrow a canard porn addiction skeptics often peddle) watch cute cat videos forever. They do, however, lose themselves in video slots and internet porn and social media. Why is that? What makes some ludic loops so much more likely than others to arise, persist, and become problematic? To answer those questions, we’ve taken a stab at modeling the factors we believe contribute to the existence and durability of ludic loops. This model isn’t particularly scientific (not even in the “dismal science” sense), but we hope our readers will see it as a reasonably constructive first pass at bringing some order to the complex origins of porn binges and other internet black holes that resemble the ludic loops Dr. Dow Schüll describes. For starters, let’s go back to Dr. Dow Schüll’s explanation of a ludic loop as being “hooked into doing something that has no real reward, and the feeling of being trapped in that state of empty limbo becomes the reward in and of itself.” A simple inequality reflecting that explanation might look like this: LV > AV Where LV (“Loop Value”) stands for the value to the user of staying in a ludic loop, and AV (“Actual Value”) stands for the value to the user of achieving the “goal,” if any, of the underlying behavior. To add precision to this inequality, based on personal experience, we suggest inserting a second variable such that a ludic loop forms and endures when: LV > AV + PC where PC (“Perceived Cost”) stands for the user’s immediate perception of the cost of staying in the ludic loop. In our experience, when PC is obvious, immediate, and tangible to a user – “If I keep scrolling I’ll be late for work” – the loop can break. Even if there is no value (or “reward”) in the underlying behavior, if the user clearly perceives the cost of entering and staying in a ludic loop as greater than the value of doing so, the loop won’t occur or persist for long. Digging deeper on the left side of the inequality, we further propose LV consists of the sum of two variables:

LV = PV + SV Plugging that equivalence into our original inequality suggests a ludic loop will arise and endure when: PV + SV > AV + PC Finally, we propose that SV and PC are inversely related. The more salient the looping behavior for the user, the less likely the user is to perceive the cost of remaining in a loop involving that behavior. Users will instead tend to discount the cost of staying in a ludic loop as salience increases. This relationship might be thought of as reflecting degrees of impulsivity displayed by the user. To summarize, according to our proposed model, a ludic loop will form and endure when the self-regulating (PV) and attention-holding (SV) attributes of the loop together exceed the value of the “goal,” if any, of the underlying behavior (AV) and the perceived costs (PC) of staying in the loop. The greater the difference between the left and right sides of the formula, the more or less likely it is that a ludic loop will form and endure. Also, because salience and perceived cost have an inverse relationship, high salience (through any combination of its primal importance to the user, its ease of access, or its engineered design) is a reasonably good predictor of the likelihood that a ludic loop will form and become problematic. Let’s put our model to the test with a real world example. As we noted above, Dr. Dow Schüll’s description of a “ludic loop” matches the experience of a “porn binge.” Under our model, a ludic loop based around consuming internet pornography might therefore arise because PV is high (the user has a need to self-regulate) and SV is high (sexual arousal is a deep primal mechanism and internet porn is freely accessible and infinitely variable), and though AV (achieving orgasm) may also be high, PC, as it is inversely related to SV, tends to be low (or at least lower than it would be outside of the loop). As another example, take social media consumption. Under our model, a ludic loop based around Instagram use may especially arise in teens because PV tends to be high in that population (the need to regulate the hellish angst of adolescence) and SV is usually also high (the extreme desire for social approval and knowing what’s going on), whereas AV tends to be relatively low (there’s little genuine social connection in social media interactions), as is PC (perception of cost tends to be low in teens generally). Through this model, we might also tease out why it’s rare (albeit not impossible) for a ludic loop to arise and become problematic around, say, looking at cute cat videos. While the PV of a ludic loop involving looking at cat videos may be high (since it doesn’t depend on the content but rather the condition the user seeks to escape), the SV of cat videos is relatively low and declines over time (because cat videos tend not to be particularly variable in their content). On the other side of the equation, the AV of looking at cat videos (getting a giggle and some warm fuzzies) isn’t especially high and also declines over time, while PC can be high (“ugh, I’m such a loser looking at another cat video”). Likewise, a ludic loop consisting of driving endlessly in circles is comparatively unlikely because even if PV is high (it’s nice to zone out and just drive) and AV is zero (there’s no destination), SV is minimal (driving the same route over and over isn’t so interesting) and, thus, PC tends to be high (fatigue and gas expense). The model seems to fit real world examples. So, what’s its point? First, as we said at the outset, the proposed model is our attempt to bring a little order to the topic of porn binges by sketching out variables that affect the likelihood and durability of a ludic loop generally. All too often, we’ve heard arguments about porn addiction bog down in the inherent complexities of compulsivity and sexuality. We hope this model might spur discussion about what specific factors come into play when a person struggling with porn/internet addiction disappears into yet another self-destructive binge. Second, porn addiction skeptics often reject the “addiction model” by saying “it’s not the porn” that’s the problem, but rather an underlying mental illness or personal moral conflict in the user. Dr. Dow Schüll observed a similar strain of “lopsided” reasoning in critics of gambling addiction. “The problem,” they say, “is not in the products [players] abuse, but within the individuals” themselves. We don’t discount the possibility that a portion of people trapped in porn addiction also suffer from other mental illnesses or feel moral conflict with their behavior. With this model, however, we resist the idea that inherent nature of porn-as-porn has “nothing to do with” why people binge on it. We propose that it is the porn that, at least in part, contributes to the existence, durability, and addictive nature of a ludic loop focused on internet porn consumption. Porn is highly salient. It taps into the sex drive, is easy to access, and features infinite variety in a way that attracts and holds attention – and, we propose, blunts a user’s immediate perception of cost – in a way that no cat video or drive around the block ever will. Third and finally, we hope this attempt at modeling porn binges and other internet-based ludic loops might help clarify the origins of problematic pornography-related behaviors. Taking a lead from Dr. Dow Schüll, we wonder whether certain porn use behaviors become addictions not simply because of the content of internet porn, or because of the particularities of the user, but because of the interaction between the two. To be more blunt, we wonder whether a “ludic loop” may best be thought of as a “drug of addiction” that delivers a sought-after “high” for problem porn and internet users. It may not be the only “high” those users pursue, and other problem porn users may ignore its availability altogether in favor of the euphoria of reaching orgasm. But, in our experience, for many struggling with porn addiction a primary purpose of using porn is – like Dr. Dow Schüll’s video slot players – “to climb into the screen and get lost,” only to emerge when an (unwanted) orgasm or exhaustion breaks the loop and returns them to an increasingly dismal reality. As always, we encourage constructive feedback and polite discussion in the comments section. This week brought news the World Health Organization has officially recognized in its newest diagnostic manual, ICD-11, the diagnosable condition known as Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (“CSBD”). We are heartened by this development because it takes a meaningful step toward ensuring people struggling with what we refer to as “porn addiction” receive the help they need. It also serves as a long overdue validation for anyone who felt the pain and confusion of reading, over and over, that their agonizing, unceasing compulsion to consume porn wasn’t “real.”

Here is how ICD-11 describes the very real condition known as CSBD: Compulsive sexual behavior disorder is characterized by a persistent pattern of failure to control intense, repetitive sexual impulses or urges resulting in repetitive sexual behavior. Symptoms may include repetitive sexual activities becoming a central focus of the person’s life to the point of neglecting health and personal care or other interests, activities and responsibilities; numerous unsuccessful efforts to significantly reduce repetitive sexual behavior; and continued repetitive sexual behavior despite adverse consequences or deriving little or no satisfaction from it. The pattern of failure to control intense, sexual impulses or urges and resulting repetitive sexual behavior is manifested over an extended period of time (e.g., 6 months or more), and causes marked distress or significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. Distress that is entirely related to moral judgments and disapproval about sexual impulses, urges, or behaviors is not sufficient to meet this requirement. Critics of the new CSBD diagnosis hasten to point out that ICD-11 omits any mention of the word “addiction” in relation to CSBD and categorizes CSBD as an “impulse control disorder.” According to the critics, these features purportedly reflect the WHO having rejected the “addiction model” as an appropriate approach to treating CSBD. There also seems to be a vein of dismissiveness in these criticisms, as if an “impulse control disorder” is somehow less serious than diagnoses labeled “addiction” – which seems odd, considering “impulse control disorders” also encompass serious conditions like kleptomania and pyromania. Still, clinicians who already have been treating patients suffering from “sex addiction” and “porn addiction” for years are celebrating. The lack of an “addiction” label on CSBD notwithstanding, it’s indisputable CSBD’s diagnostic criteria address the type of uncontrolled sex-related behaviors these clinicians have long been addressing, with at least some success, through addiction-related treatment modalities. Likewise, many, likely most, of those men and women who belong to sexual behavior-related 12-Step fellowships such as Sex Addicts Anonymous would easily recognize themselves and their fellow group members in the CSBD definition. The fact is, even though the word “addiction” remains a fixture in our society, the term long ago fell out of favor as a diagnostic descriptor. For instance, clinicians today refer to the condition everyone colloquially calls “drug addiction” as “substance use disorder.” The thinking among therapists and doctors goes that the label “addiction” stigmatizes patients (although, ironically, it’s not unusual for patients to take comfort from that word…but that’s a topic for another day). It’s also worth noting that the CSBD criteria flat out reject the tired canard that religiosity alone motivates people to seek help for “sex addiction” and “porn addiction”. According to the definition above, CSBD stands apart from merely wanting, and failing, to quit porn on moral grounds. (Which is not to denigrate anyone’s religious motives for wanting to quit porn – they’re just not what qualifies as CSBD without other factors present.) We look forward over the coming months and years to learning what percentage of prospective patients who seek help from therapists for uncontrolled sexual behaviors meet the diagnostic criteria for CSBD. We suspect the figure will be far higher than critics of the CSBD diagnosis predict. But, even if CSBD only affects 1% of the internet porn using population worldwide, that’s still tens of millions of people around the globe.

Here at PornHelp, we have our worries about the potentially harmful effects of prolonged porn use among young people. We recently heard a statistic from a credible source that only served to heighten that concern: online porn platforms estimate that 25% of their users are underage. Considering the truly massive use and visitor statistics touted by the likes of PornHub, that would suggest the porn platforms know they have millions upon millions of kids accessing their content.

That’s a huge number, but it’s probably not all that surprising. What did surprise us, though, is what our source told us next. Apparently, porn companies are also saying that they do not want young users on their platforms. Now, you might think porn platforms would say that because, well, it’s the right thing to say. After all, across political, idealogical, and methodological spectra, there is nearly universal agreement that it’s not a good thing for children to have unfettered access to pornography. But, that isn’t what we heard from our source. Instead, porn platforms make a business case for why they don’t want young users. As readers of this blog know, today’s internet porn sites are principally advertising platforms. The argument from the porn platforms apparently goes that underage users are not good sales leads. Advertisers trying to appeal to an audience with ready access to a credit card to purchase “premium” content will pay less per ad click if they know that roughly a quarter of those clicks are by users too young to have a credit card. Fair enough. We’ve seen Glengarry Glen Ross. Bad leads are the cancer of any sales operation. But, we have our doubts about the sincerity of the “kids are bad leads” argument. After all, we used to watch Saturday morning cartoons. Our parents weren’t watching Power Rangers. They weren’t seeing the ads for Go-Gurt. They weren’t digging on the newest My Little Pony accessory. If advertising to children wasn’t profitable, Saturday cartoons wouldn’t exist. Now, we acknowledge that the mode of advertising during Sponge Bob was different than what we’d expect from a porn platform. Sponge Bob’s advertisers were hoping we’d badger our parents into buying fruit snacks and G.I. Joes. Obviously, kids aren’t going to be asking their parents to please buy them a subscription to Brazzers. But still, there are plenty of advertising relationships that could be profitable for an online business with a captive audience of millions of under-18s. Video game and app producers. Social media platforms. Energy drinks. Etc. So, when we hear that porn platforms say they don’t want the 25% of their users who are underage, we’re skeptical. Call us cynics, but we suspect porn platforms are monetizing young users just like any other advertising cohort. If you know a quarter of your audience is between the ages of 8 and 17, you’ll sell access on your site to advertisers who want to target that audience. Not only that, assuming you can reliably identify underage users on your platform, you’ll track their behaviors on your site and collect behavioral data that you can further turn into dollars. If you are vertically integrated, you will produce more of the porn content that your data tells you those users like. In short, you’ll treat that 25% of your audience as an asset, just like the other 75%. We recently had an unpleasant Twitter exchange with two prominent porn addiction critics. We don’t need to go into the details (if you’re interested, see here), but it ended with one of them challenging us to “show our commitment to inquiry” by describing any, even just one, “positive effect”of “sex films”. Our critic presented this as something of a litmus test to determine whether or not we were “trolls”, and promised to send us research if we could deliver.

Now, we don’t feel much need to defend ourselves against attacks on our intellectual honesty. Our blog posts speak to our commitment to inquiry quite adequately, thank you very much. Also, since our founding one of our organizing principals has been that we avoid making black or white pronouncements about pornography use. It’s not that we don’t have views on this issue (see below). Rather, we think it’s best not to stake out hard positions lest we be seen mistakenly as judging porn users and thereby deter people struggling with porn from finding help on our website. We’re here for anyone who feels their porn use is problematic, no matter the cause. We suspect some of our users love porn but can’t control how they use it, some hate porn and want to eliminate it from their lives, and most are probably somewhere in between. And yet, it’s undeniable that our Twitter feed betrays some pretty clear beliefs. Most of the research and commentary we share in one way or another reflects views that put us pretty squarely in the corner of porn skeptics. To wit:

So yes, we are highly porn skeptical here at PornHelp.org. But we also don’t like to back down from a challenge. The “spirit of inquiry” does require us to look at problematic porn use from as many perspectives as possible. That includes, today, the perspective of those who view pornography as a social benefit. So, for the sake of provoking searching (and respectful) debate, and to respond to anyone who might otherwise consider us “trolls” merely because of our strong porn skepticism, here are some ways in which we’re able to conceive that “sex films” - i.e., modern streaming internet porn - may have a “positive impact” (which, just to be clear, is not to say that we believe these effects result in a positive net impact). Ready? (Deep breath.) Here goes. For starters, internet pornography constitutes a comprehensive visual compendium of human sexual practice, from the mundane to the highly niche. This sort of visual library of sexuality sheds light on, and facilitates the study of, the human condition. We value study and debate on all topics, including historically taboo areas like what goes on in people’s bedrooms and what triggers people’s sexual response. So that’s something positive that porn - however unintentionally - can lend to the world of knowledge. Next, we acknowledge it’s not just researchers who may find value in the internet’s endlessly diverse collection of porn videos. Consenting adults can use “sex films” as a source of mature, responsible sexual stimulation, and as a way to explore - and affirm - their sexuality in relative privacy and safety. To be sure, we don’t think the intense stimulation and mind boggling variety (not to mention the 24/7 accessibility) offered by internet porn are inherently positive attributes (for many who seek help on our site, they decidedly are not), but we recognize they potentially can be for some people. Finally, we recognize the possibility of certain positive impacts from producing pornography. Porn is a big business, and in cases where its labor force is healthy, safe, consenting, and justly compensated (which is not the norm), and where its consumers acquire their porn through distribution channels that pay producers for their creations (also not the norm), the broader economy can benefit. Also, porn-producing adults may derive sexual pleasure or emotional satisfaction from being filmed in a sex act, or in treating their pornographic creations as a form of artistic expression. That's not our jam, but we're not going to judge. So there you have it. Not just one, but at least three ways in which our spirit of inquiry compels us to contemplate positive impacts from “sex films.” We’d say that pretty definitively takes us out of the realm of troll-dom, even if it doesn’t make us any less skeptical and concerned about porn’s overall human impacts. To anyone who would say that we’re betraying our mission by acknowledging potential counterpoints to our beliefs, we invite (respectful) debate in the comments section. We think intellectual candor is the cornerstone of any honest debate, so we feel confident our readers will understand the purpose in our willingness to go through the looking glass today. We’re somewhat less confident that our Twitter antagonists will ever send us that research they promised, but there’s always hope… One last thought in parting. At the top of this post, we rejected absolutism about pornography use. We did that in service of a mission in which we are absolutists: our guiding principle that people who feel porn is interfering with their lives and want help, deserve to find that help no matter how or why concern about their porn use arises. Period. Maybe some of those people will find their porn use isn’t personally problematic after all. We suspect many more will come to the opposite conclusion. But in either case, we will take pride if they were able to find the help they needed here on PornHelp. |

AuthorLonger-form writing from the PornHelp team on current topics relating to problem porn use and recovery. Archives

June 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed