|

We have not joined in recent calls to shut down PornHub and its parent company, MindGeek. Not because we disagree with those who speak out against the companies’ chronic failure remove abuse imagery from their sites. Rather, because our mission is to help people who struggle with compulsive, obsessive porn use. As a rule, that means we try to avoid labeling pornography, or its purveyors, as inherently “bad” or “wrong”, because those words easily lead to shame for users, which in turn feeds into the relentless, destructive tug of addiction.

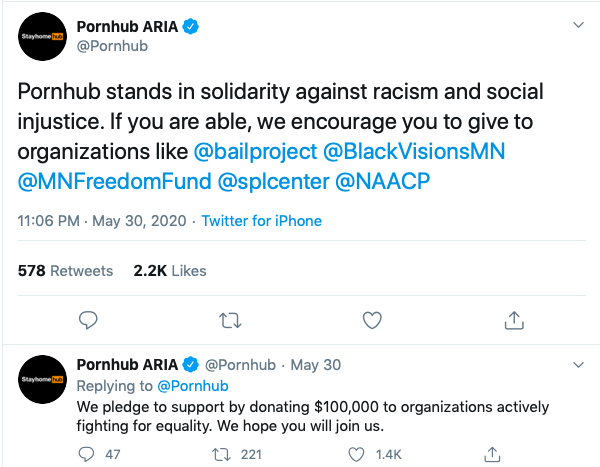

However, this has been a particularly terrible week in America, even in the midst of what feels like an unrelenting series of them. The outrage over the killing of George Floyd, and the mayhem that has followed on the heels of public protest, has us feeling as anxious, even despairing, as ever. Then, like a bad dream, PornHub somehow managed make things even worse. To speak bluntly, that really pisses us off. So, please indulge us as we vent our spleen. In tweets pinned to its official “ARIA” Twitter feed this weekend, the behemoth of the porn industry expressed its solidarity with protesters marching in cities throughout the U.S. PornHub’s official Twitter account encouraged followers to donate to venerable civil rights organizations like the NAACP and the Southern Poverty Law Center. It even pledged a $100,000 donation.

In normal times, we would not blink at this sort of crass corporate virtue signaling. But these are not normal times. And PornHub/MindGeek is not just any company. PornHub and its affiliated sites promote, distribute, and profit from some of the internet’s most virulently racist and racially exploitative content. The pantomime of racial solidarity it tweeted-out was not just an example of poorly-conceived, moment-seizing PR. It was a glaring example of perverse cynicism.

PornHub hosts gigabytes of “interracial” videos, many featuring the “N-word” in the title, depicting slavery-related themes, or deploying the most offensive racial stereotypes imaginable. It collects, archives, tags, and categorizes thousands of hours of “casting couch” porn, in which the central premise is the exploitation of a young, poor, brown-skinned woman by an older, powerful, white man. It offers up endless streams of globe-trotting “gonzo” porn in which sex workers plucked from the streets of impoverished Third-World locales submit to what appears to be (and likely is) extreme sexual violence for the camera. And on and on. We’ve previously written that PornHub tweeting support for civil rights organizations feels akin to Harvey Weinstein delivering the keynote speech at an anti-sexual violence event. But really, that attempt at gallows humor does not begin to capture how debased and amoral a person has to be to express support for a protest movement focused on the very ideas and images that same person relentlessly blasts into the public sphere every second, for profit. Seriously, people who work at PornHub/MindGeek, what the hell is wrong with you? Do you have no sense of decency? Do you so lack for empathy that you do not appreciate the profound pain, lived by your fellow human beings over generations, that has spurred the protests against George Floyd’s murder at the knee – the knee – of a police officer? Does it not occur to you how harmful it is for your sites to collect, and neatly-organize-for-easy-browsing, overtly racist content? Do you not appreciate the anti-social depravity of your algorithms pushing content that glorifies racial exploitation, over and over and over and over? Do you really not see that you are a massive part of the problem? We have to think that someone working for PornHub/MindGeek has an ounce of humanity, or at least a passing appreciation for the value of showing some basic integrity. So perhaps that person will hear this message: PornHub/MindGeek, either use this searing moment in history to put your own damn house in order…or do us all a favor and shut up.

1 Comment

A recent article written by Bowling Green State University professor Dr. Joshua Grubbs for The Conversation rejects concerns about the long-term effects of a rise in online porn use during the coronavirus lockdown. The commentary dismisses the notion of “widespread problems” associated with porn use, and suggests that watching porn may have a public health benefit by offering quarantined people an internet-enabled, socially-distanced alternative to in-person sexual intimacy. It also predicts a return to pre-pandemic levels of porn use once lockdowns and social distancing measures end.

These contentions deserve further examination. In the wake of coronavirus lockdowns confining millions to their homes, PornHub (flagship website of the porn juggernaut MindGeek) reported large increases in traffic to its site. PornHub undoubtedly juiced its own growth by offering free access to “premium” content to users in quarantined areas (the site has always offered vast amounts of “free” content). At any rate, the site claims traffic increased as much 24.4% over its daily average, representing tens of millions of additional page visits per day. Grubbs’ article in The Conversation asks whether that marked rise (which, presumably, reflects an increase in porn consumption internet-wide, not just on PornHub) will lead to negative outcomes for porn users in the long-run. Citing his own and others’ research, Grubbs predicts it will not. In his view, pornography does not cause “widespread problems” such as addiction or sexual dysfunction, but rather, constitutes a harmless “distraction” for “most” users. In that respect, the article contrasts porn use to the coronavirus pandemic, arguing that the former does not constitute a public health crisis, whereas the latter undoubtedly does. While by-no-means do we equate contracting a deadly virus with consuming online porn, we nevertheless disagree with that proposed dichotomy. If living through the pandemic to this point has taught us anything, it is the vital importance of measuring a problem in order to figure out how to manage it. COVID-19, in all of its horror, will likely cause severe health outcomes for a relatively small percentage of the world’s population. “Most” people will not end up intubated or dead. Yet, no one doubts the extreme threat of the potential outcomes of the virus, because as any scientist well knows, percentages require the context of raw numbers. And those, unfortunately, paint a terrifying picture of a disease that will cause destruction and suffering on a previously-unimaginable human scale. That is why every coronavirus news report cites tallies of confirmed cases and deaths, not percentages of people afflicted. It might not sound like a lot to predict the virus will kill one-tenth of one percent of the U.S. population, until you do the math and realize that means losing 350,000 Americans and enduring unfathomable suffering in our families, communities, and economies. The same logic must apply to assessing the potential impact of an increase in use of online pornography (or any other potentially problematic behavior, for that matter). Absent from the article in The Conversation is any discussion of the scale of problematic behaviors focused on porn consumption. Grubbs, however, implicitly acknowledges that the number of users who develop problematic behaviors involving porn consumption is not zero (extensive research confirms as much); in which case, back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest a potentially significant problem. Estimates gauge that about half of the world’s population has internet access. If ten percent of those users (roughly 350 million people) view pornography, and one percent of those develop problematic behaviors…you see where we are going. (PornHub's widely-touted reports of hosting tens of billions of user visits annually would seem to bear out those rough estimates.) In light of the scale of worldwide porn use, we believe the article in The Conversation ought to give anyone familiar with addiction science more cause to worry, not less. Grubbs notes that people turn to online porn use to cope with negative emotions such as stress, anxiety, and depression, all in ample supply during the pandemic. That troubles us, because research has long observed that a motive to blunt or cope with negative emotions often lies at the heart of substance abuse and behavioral addiction. These disorders, writ-large, certainly constitute a legitimate public health concern with far-reaching social and economic impacts that we ignore at our peril. By the same token, until we know just how many people’s porn use will turn problematic in the same manner as other disordered, addiction-like behaviors, we do not see how it is possible to say with any confidence that a sharp rise in that use will not lead to a volume of negative outcomes worthy of public attention and concern. One cannot argue that all is well just because “most” porn users do not report problems in their lives stemming from their consumption (and again, how many is “most”?). The same could be said of drinking alcohol, but that does nothing to diminish the real risk our current plight poses for anyone prone to alcoholism. Let’s not forget, too, that PornHub undoubtedly aims not just to boost existing use, but also to capture and keep new users, by offering “free” content to the quarantined masses. Online pornography distribution is a business, after all. Big porn sites monetize their customers by selling subscriptions and ad space, and by hoovering up user data. They see the pandemic as an opportunity to grow customers and profits not just temporarily, but for the long-term. That is why, to anyone whose life has suffered tangible harm from problem porn use, PornHub’s giveaway smacks of a drug dealer offering a free taste. The crass opportunism of mining a deadly health crisis for financial gain worries us all-the-more because, as Grubbs points out, another (arguably) negative emotion, boredom, may also play a key role in spurring PornHub’s boost in traffic. Who has the market more-or-less cornered on that particular state of mind? Young people, that’s who. Millions of them presently sit cooped-up at home, missing their friends, bored out of their minds, and capitalizing on rising screen time to find a “distraction.” Unfortunately, those same young people also happen to constitute the population most vulnerable to being misled, manipulated, or traumatized by hardcore porn content. In other words, if Grubbs is right that boredom fuels (new) online porn use, then PornHub’s new users could very-well consist disproportionately of the people least emotionally-prepared to consume its product. We also beg to differ with Grubbs’s prediction that porn use will return to “pre-pandemic” levels after lockdowns lift. For one thing, the porn industry is a billion-dollar behemoth with a vested interest in making sure that does not happen. MindGeek and others will surely pull out the stops to lock-in their gains. For another, as of this writing, no one seems to have much certainty about when the coronavirus disruption will end. The uncertainty of that timeline must constitute an important variable in any analysis of whether rising porn use will cause long-term problems. Perhaps it is true that a week, even a month, of relying on porn as one’s sole sexual outlet might not lead to lasting problems. But how about three months? Six? Twelve? Plus, even after the world “reopens,” what are the odds that anyone will feel as liberal with their personal space as they did before? We can’t speak for others, but we suspect the anxiety and urgency we feel about maintaining a six-foot bubble is going to linger for quite a while. Which is why, having now witnessed a pandemic unfold, our nagging fear of a dystopian future in which people prefer the antiseptic thrill of virtual porn to the real thing suddenly doesn’t seem so unrealistic after all. For these reasons, we disagree that anyone should feel sanguine about PornHub’s spike in traffic, as the article in The Conversation urges. As yet, we know little about what the “new normal” post-pandemic will look like. Assuming pre-pandemic research represents an accurate base-case for predicting future porn use patterns, however, what we do know is that a growth in porn use and users also means an increase the real numbers of people affected by unhealthy porn use behaviors, and in the collateral effects of those difficulties. As with the coronavirus, until we obtain an accurate measure of the scope of that problem, we cannot know how best manage it, much less feel reassured that it will manage itself. [Ed. Note: In the spirit of open and vigorous debate, we invited Grubbs to comment on this article prior to publication. Quoted below is a portion of his response that he authorized us to share publicly. “I do think that the base rate argument makes sense. Even if only 20% of Americans use pornography regularly and only 1% of those users ultimately develop problems, that still produces a large number (roughly 700,000 people) experiencing pornography related problems in the U.S. alone. If you examine the entire developed world (where pornography is widely distributed), this number would accelerate into the millions quite quickly. Ultimately, this is one of the major arguments we are trying to articulate in the addiction science and clinical psychology communities. It’s a fine line to tread, acknowledging these fields’ skepticism of compulsive sexual behavior disorder and pornography use problems, while also demonstrating that, for some users, the problems are real and warrant clinical attention. I’ve been transparent with most folks who dialogue with me about these issues that my primary objective during the past decade of research has been to get addiction science and clinical psychology to take pornography use seriously. My approach to doing that has been to build a body of research that both validates skepticism of pornography addiction while also pointing to the notion that pornography related problems are very real and worthy of attention. It is my opinion that we have finally reached that point. We have work recently released in the Journal of Abnormal Psychology and forthcoming in Clinical Psychological Science (both are top-tier clinical psychology journals) that do exactly this. Ultimately, I think that pornography addiction models will be widely accepted within clinical psychology and addiction science more broadly over the next decade, but the first step to getting to that point is to get the fields to talk about the issues in general. Which model of addiction will be accepted is still up for debate (I personally do not like the Brain Disease Model of Addiction for any addiction), but that’s where we are moving, and we finally have the traction to do so.”]

Not gonna’ lie, this coronavirus thing has us thrown for a loop. Anxiety feels like our baseline emotion at the moment, which presents challenges both when we need to get work done and when we want to relax. We suspect we’re not alone feeling this way.

No, check that, we know we’re not alone. In recovery from compulsive porn use, we recite the importance of “connection” as a mantra. Literally, “the opposite of addiction is connection” (a deceptively complicated truism, to be sure). Coronavirus social isolation measures have knocked that maxim askew. 12-Step meetings get cancelled. Socializing with friends or extended family goes out the window. Everyone has been ordered to work from home. Addicts of any stripe face heightened risk right now. But, those of us who have struggled with screen-based addictive behaviors face a double-challenge. Suddenly, we find the only means of connection available to us – a screen and the internet – are the ones that caused us so many problems in the first place. Not an ideal situation. Still, it’s the world we live in at the moment, and we all know the importance of accepting the things we cannot change (speaking of mantras). So, let’s look at some solutions to keep ourselves sane and sober until this thing blows over. First, 12-Step meetings. Even if your 12-Step group has cancelled in-person meetings (most have, at this point), all of the major 12-Step fellowships offer online and telephone meetings. We have reports of individual meetings coordinating to host their own group teleconferences. If your meeting needs help figuring out how to make that work, let us know and we’ll hook you up with help. Second, therapy. You probably cannot meet in-person with a therapist for the foreseeable future. But, here’s a silver lining. The coronavirus outbreak has accelerated “tele-health” availability to warp speed, giving you the option of meeting with a qualified addictions therapist via video chat. Seriously, this sounds weird, but now is a GREAT time to try therapy. Check out our listings here for porn addiction/sexual compulsivity specialists who treat people in your state/country. Can’t find someone who fits your needs? Email us ([email protected]) and we’ll work to get you connected with help. Third, online forums. Look, straight-up, we have never been huge fans of trying to manage quitting porn entirely online. Still, forums like NoFap and Reboot Nation provide essential support and community, especially during this unusual moment. If you haven’t tried them out yet, now is the time. Share tips. Get connected with someone like you. Make new friends (we’re not kidding). Fourth, not all of life needs to happen indoors. You still have plenty of options for balancing the nouveau isolation with healthy pursuits outside in your free time. Go running. Plant a garden. Draw sidewalk art. Give bird-watching a try. We could go on, but you get the idea. Many of us have the impulse not just to self-isolate, but to crawl under a proverbial rock and wish the world would just disappear. Resist the urge. You know where that leads. Finally, use the internet for good. Send someone – a loved one, a veteran, a doctor, a famous writer – a note about how much you appreciate them. Contribute to efforts to help those in need. Teach a parent or relative how to start a video chat. Film yourself making a family recipe and share it with your siblings, friends, or grandkids. Technologists dream of an internet that brings humanity together, instead of driving it apart. Armed with knowledge gained through long and sometimes painful experience, this our moment to act as a force for that change. Time to step up.

We have been active, of late, calling attention to the business end of the porn world. Over the weekend, news arrived that a trove of data from a Spanish “camgirl” website tying user data to usernames had been made public. This was hardly the first data breach in the industry.

Some may read that news and and shrug. “Why should I care if my porn site browsing data is out there?” Viewed in isolation, that might be a semi-reasonable perspective. The world is awash in data, after all. How are a few more bits and bytes floating around in the ether going to hurt you? Here's how. Data collected about your movements on a porn site doesn’t exist in isolation, but rather alongside the vast amounts of data your other, non-porn internet and internet-of-things (“IOT”) activities generate. Data aggregators collect as much of that data as possible from as many sources as will provide it. They package that data into detailed profiles of you for sale to advertisers or, really, anyone who wants to buy it. These profiles are very specific. They include information about your usernames (which, let’s face it, often identify you), age, race, religion, gender, income, credit profile, residential address, occupation, employer, buying habits, and marital and family status. They track the devices you own and use to access the internet, and the apps you use to communicate with friends. They identify physical locations you frequently visit by tagging your activities with GPS coordinates. Depending on what was contained in that user agreement you “Accepted” without ever having read it when you installed a new app or set up an IOT device, a tech company might have the ability and (worse) the legal right to read your texts and listen to your conversations. So, not to be all apocalyptic, but it doesn’t take much imagination to come up with myriad ways a bad actor with your porn site browsing data – who also acquires all of the other information available about you that’s for sale – could compromise your life. We’ve yet to see some of the scenarios below bubble up to the surface in news reports (although there are scams that mimic them), but that doesn’t mean they don’t (or won’t) happen. The Blackmail Scenario Say you are lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, or questioning but have not yet come out to your friends, family, and colleagues, many of whom you worry would not accept you. You live in a state that doesn’t have robust anti-discrimination protections for sexual minorities, and work at a job where revealing your sexual identity would likely subject you to abuse from coworkers. For now, the internet has served as your principal mode of expressing and exploring your sexuality. Sure, your porn consumption habits make clear your sexual preference, but by-and-large it feels anonymous and safe to live that part of your life online, for now at least. Then, one day, you receive an anonymous communication from someone threatening to “out” you if you don’t pay a ransom in Bitcoin. The anonymous blackmailer knows where you live and work, and can recite to you not just the porn sites you’ve visited, but what videos you watched, and for how long, and how many times. Think you might pay to keep that information secret? The Messy Divorce Scenario Say you and your wife are going through an angry divorce. You have a daughter together. You want shared custody. Your wife wants sole custody. The family court is going to have to weigh your and your wife’s fitness as parents. The data collected by a porn site you have visited includes information about from where and how long you’ve browsed, and what, specifically, you’ve watched. You aren’t proud of it, but once or twice while at home late at night you’ve browsed the “Incest Porn” category, where adult performers act out “daddy/daughter” scenarios. It’s one of the porn site’s most popular genres. Think that information would be useful to your spouse’s lawyer if, say, someone offered it to your spouse for a few hundred bucks? The Cyber-Stalking Scenario You are young and single, living alone in a new city where you don’t know many people yet. One night, on a lark and after a few glasses of wine, you go to a “cam” site where you have a “cybersex” encounter with a performer in exchange for “tokens” you purchased on the site with your credit card. You don’t show your face, but the performer (and anyone else with access to the video stream) can see your body and features of your bedroom, including the open jewelry box you keep on the nightstand by your bed. In an unguarded moment you tell the performer about living alone. You enjoyed yourself on the site. You might even go back. But the credit card information you supplied when you bought tokens identifies you by name. It’s a snap to tie that information to a physical address. And now you’ve given someone an easy way to know when you are at home. Alone. In bed. And that you have nice jewelry. Think you might have put yourself in danger? The Employer Surveillance Scenario You used your work device to surf porn while on a business trip. It was a stupid thing to do, you immediately regretted it, and you cleared your browser history immediately afterwards. No worries, right? Well, maybe not. A third-party web marketing company that contracts with the website you visited installed a tracking applet on your device when you clicked “OK” to enter the site. While you roamed the porn site, the third-party applet collected unique identifying information about your device, down to its serial number. Unbeknownst to you, the marketing company sells that information to a cybersecurity firm your employer pays to monitor the use of devices it gives to employees. Think you have “no worries” now? The Manipulation-for-Profit Scenario You enjoy watching porn videos showing performers using sex toys. That’s not something you’ve ever tried in real life, but maybe one day. The porn site notices your preference for sex toy-related content. Every time you return to the site, its algorithm puts sex toy videos in the exact location on your browser screen where it knows, from tracking you, that you will navigate your pointer when you arrive at the site. You don’t even realize it, but you are being fed content that appeals to you in a manner precisely calculated – down to the square inch of screen-space – to match your browsing behavior. Maybe that creeps you out. Maybe it doesn’t. But here’s something else. The porn site has an advertising deal with a specific brand of sex toys. All of the videos pushed to you feature that brand. It’s a subtle thing. The videos don’t identify themselves as ads. You don’t even see any brand logos on the toys. But then one day the exact same toy you just watched someone use in a video you “favorited” shows up in a banner ad on the side of the page. 20% off! Maybe it’s time to give that toy a whirl. Think your deepest desires have just been harnessed to sell you something? Look, here’s the bottom line, as paranoid as it might sound. When you watch porn, porn watches you, too. In fact, that’s the whole point. Porn site operators make money by knowing (or having the ability to know) exactly who you are and what stimulates your deepest urges. In exchange, they push content to you for “free,” assuming you’re cool with having zero control over who sees the information they have about you and how that information gets used. To assume an online, porn-related breach of privacy that damages your life would never happen to you is to have faith that everyone you encounter on the internet has the best of intentions. Think that’s actually true?

Ask anyone to recall a difficult moment from their teens and early twenties, and there is a high probability their minds will go to an incident relating to sex. Even if the memory does not relate to specific sexual activity, it will have something to do with the unfathomable vicissitudes of living with a still-developing sex drive. For some, those recollections will involve the trauma of sexual violence. For others, the lucky ones, mere embarrassment, anxiety, or confusion.

We’re generalizing, of course, but our point is that most humans experienced an emotionally-fraught, sex-or-sexuality-driven episode (likely more than one) in their teenage and young-adult years. It’s something we all broadly share, along with the challenge of putting those difficult experiences into context and coming to grips with how and why they affected us. The psychotherapy industry sustains itself in significant part on helping people “work through” these experiences. It’s November 1, which means that today young men around the globe will embark on the #NoNutNovember, challenging themselves to abstain from masturbatory orgasm (or orgasm altogether) for an entire month. Only few will succeed in becoming “Masters of Their Domain,” to use the Seinfeld-ian term that presaged #NNN. In years past, commentators have debated the ontological underpinnings of young men’s desire to engage in #NoNutNovember. Do they refrain from orgasm in service of healthfulness? Moralism? Misogyny? Frankly, we find all of those arguments a little too reductive. From our perspective, it doesn’t much matter why someone decides to participate in #NoNutNovember, or in temporary sexual abstinence generally, so long they capitalize on the experience by becoming more mindful of their own sexual impulses and embarking on the deeply human task of coming to terms with their sexualities and how their actions affect themselves and (just as importantly) others. We are living through a reckoning about (mostly male) sexual misconduct in America and (though to a lesser extent) globally. There have been, of course, widely-reported revelations about criminal sexual predation. But also, the #MeToo movement has shined light on varying perspectives of what is and isn’t “acceptable behavior,” and on how we interpret and judge each other’s actions relating to sexuality. (See, for example, the cases of comedians Louis C.K. and Aziz Ansari.) It doesn’t break new ground for us to observe that some men struggle to understand and participate fully in discussions of sex-behavioral expectations. You could write volumes on the sources of this difficulty – toxic masculinity, gender normativity, neuroscience – without scratching the surface. It’s an immensely complex topic. That said, we think #NoNutNovember holds promise as a tool for men who might otherwise struggle to comprehend sex-related behavioral expectations. It’s a potentially blunt instrument, to be sure, but approaching abstinence from masturbation and orgasm the same way you might, say, take on the “Whole 30” diet or a juice cleanse, presents an opportunity to be mindful about your sexual impulses. Whether or not the health benefits are real or merely perceived, at least you are stepping out of a comfort zone and forcing yourself to think actively about your behavior. In other words, if tackling #NNN leads you to ask yourself “Why is my hand on down my pants right now?” or “What was I thinking about just before I reached for my phone to look at porn?”, then all the better. The answers to those questions offer insight into your actions. They open up new perspectives. And they often lead to even more questions that can prove revelatory:

These are important questions. The effort and introspection required to answer them (not to mention the answers themselves) lead in the general direction of the maturity and self-acceptance that lie at the core of human experience. And they might just make you a better person, a better friend, and a better lover, along the way. So, good luck to all of you #NoNutNovember “fapstronauts.” Take care. Be mindful. And remember, it’s the journey, not the destination, that matters most.

By now, you’ve probably heard about and watched the Super Bowl commercial for frozen dinners that mocks porn addiction. Just in case you haven’t, here are links to the 30-second ad that aired nationally, and to the “uncensored” 60-second spot that Devour Foods (owned by Kraft Heinz) produced and distributed online, including on PornHub.

When we first saw the 60-second version, which was released about a week before the big game, we took issue with it on Twitter. We didn’t object to how it poked fun, necessarily, but rather, to its choice of mockery as a medium. We want to expand on that here. As a rule, we rarely take issue with laughing in the face of addiction. Humor has real power in recovery as a means of reminding us of the absurd and painful decisions we made in the throes of acting out. (A recent podcast episode from This American Life illustrates the complex relationship between humor and tragedy in addiction better than we ever could. Give it a listen.) But, it’s one thing to laugh at addiction as a tactic for undermining its power, and quite another to mock the pain of someone struggling with addiction and its destructive effects. Imagine if Devour and its ad agency DAVID had created a commercial in which the “girlfriend” character complains through tears and a black eye that her boyfriend becomes a violent “foodaholic” when he eats too many mediocre frozen dinners. Or one in which an impoverished girlfriend bemoans how her boyfriend drained their joint savings to “gamble” on whether the next TV dinner he buys will actually taste good. Or one in which the boyfriend becomes semi-conscious from the euphoria of eating Devour frozen meals until one day the girlfriend finds him on the bathroom floor, dead. We could go on, but you get the point. Would any of these spots be considered clever or funny? Probably not. Is there a meaningful difference between these and one in which a girlfriend bemoans the pain of an obsession that makes her boyfriend withdraw from life and leads to her feeling coerced into producing “amateur food porn” with him against her will? We sure don’t think so. On Super Bowl Sunday, we watched the Devour commercial again and it made us shift uncomfortably in our seats. It wasn’t just that the ad recalled the ruinous toll our porn addictions once took on relationships we cared about. We also felt the pain of the innumerable men and women across America who winced at how the spot reflected their current reality. We’d bet our bottom dollar Devour’s ad started its share of bitter arguments. It likely also pushed people who are struggling with compulsive sexual behavior deeper into isolation, making them less likely to find help because, hey, popular culture says what they’re going through is one big joke. This week, Dr. Gail Dines and Culture Reframed issued a statement condemning the Devour ad. Dr. Dines called on Kraft Heinz to provide resources for people who struggle with very real, very painful, very destructive disorders involving compulsive porn use. We wholeheartedly support that call.

Listen up, everybody. Here at PornHelp, we are not inclined to label news as “fake” or “real.” Not for any political reason. We just find those tags uselessly reductive. They too-easily surrender our right and obligation as citizens to think critically about every piece of information we absorb over the airwaves and internets. As responsible consumers of news and opinion, we believe in always questioning a speaker’s sources, methods, and motivations, and then relying on our own analysis – not someone else’s facile label – to determine what we accept as true or untrue.

So, when we write here about how frustrating we find some journalists’ one-sided takes on porn addiction, we hasten to add we’re not calling their work “fake news.” Far from it. Any time a journalist puts fingers to keyboard to discuss porn addiction, they contribute to an important and vital civic discussion. That they’re doing so, to us, constitutes news worthy of our attention, in-and-of-itself. Unfortunately, it also seems to us that when it comes to porn use and abuse, many writers fail to do a thorough and careful job in sourcing information and deciding what facts to publish and highlight. To illustrate what we mean, today we’re going to deconstruct an article that appeared this morning in the Daily Beast about the recent college student-led movement to filter porn from campus networks across the country. But, to be clear, in conducting this exercise we’re not picking on the author, Emily Shugerman, or the Daily Beast, in particular. We could do this with any number of pieces we’ve read over the past twelve months. Shugerman’s Daily Beast article is just the most recent example we’ve seen of a lack of journalistic rigor on the topic of porn, which is why it gets the full treatment today. So, without further ado, there’s the anatomy of a questionably-sourced, needlessly reductive, downright lazy news item about porn, in four parts. Enjoy. Part One: An Enticing Opening Belies The Facts The article starts off strong with an eye-catching title and an intriguing lede about “college men” picking up the torch of resisting porn from “Republicans and radical feminists.” Sounds tasty! It goes on to report (accurately) that earlier this semester male students at Notre Dame published an open letter asking the university to block porn, that more than 1,000 men and women at the university joined in their call, and that men and women on campuses across the country have taken up the banner at their schools, too. So far so good. And yet, hold on a second. If men and women at these schools have called on administrations to filter porn on campus wifi, why is the article titled “These College Guys Are Trying to Ban Porn on Campus”, and why did the lede make it sound like we were only going to be reading about “college men”? Also, not to nit-pick, but isn’t calling what these students want to accomplish a “ban [on] porn on campus” a bit too strong, considering their aim is to filter campus wifi and they acknowledge students can still access porn in myriad other ways? Finally (as you’ll see below), that lede is, shall we say, a tad misleading in saying “college men” are taking the mantle from “Republicans” when it later describes those men as, you know, Republicans. Hmm. Seems like a bait-and-switch. Let’s read on. Part Two: Manufacturing Narrative Tension By Cherry-Picking Science Something strange happens next in Shugerman’s piece. She suggests maybe the students advocating for campus wifi filtering are misguided in their concerns about porn addiction. Citing two unattributed studies from 2013 and 2014, Shugerman argues porn isn’t such a big deal because college kids don’t actually use online porn all that much. Hold on. lolwut? If there’s one thing unassailably true about internet porn use today, it’s that college-age kids comprise an enormous portion of the user population. Didn’t Shugerman read Kate Julian’s recent article in The Atlantic about why young people are having less sex than ever? It describes in vivid detail how porn has seeped into every aspect of young adults’ intimate lives. Whatever the two studies are that Shugerman is relying on, their conclusions (at least as Shugerman describes them…we’re relying on her say-so here since she hasn’t actually provided links) is contradicted by widely-available research showing frequent porn use is common among college age people and young adults. The article then alludes to two more studies to buttress the argument that the campus porn filtering activists have little to fear from porn. One study from 2007 (again, not linked) purportedly claims porn does not predict negative attitudes toward women. The other study, from 2014, argues “perceived” porn addiction correlates with religiosity. (Shugerman fails to mention, however, that this study has been forcefully debunked and debated, particularly regarding the relevance of “perceived addiction” to, you know, actual addiction.) And that’s the extent of the “science” Shugerman cites. It’s odd, to say the least, that despite the students she interviewed mentioning “porn addiction” as a concern, none of the studies she chose to highlight actually discuss widespread evidence of problematic pornography consumption and compulsive screen use generally in younger populations. It’s not as if she lacked for dozens-upon-dozens of studies to choose from. For whatever reason, the article simply confines itself to some research only tangentially related to what students cited as a major concern for their movement. Why might that be? Wait, don’t tell us. We’re gonna guess it has something to do with reducing everything to political and cultural stereotypes… Part Three: Invoking That Same Old, Tired Chestnut …Aaaaaand, we were right. Shugerman next casts the campus wifi filtering debate in terms of left vs. right political labels. There are some convenient facts on her side. For instance, she notes that a major conservative publication picked up the story, and that it attracted the attention of a “conservative firebrand” (and female) student at Georgetown. Yet, the article could just as easily have mentioned concerns about problematic porn use on the other side of the political and cultural spectrum. (See, for example, Kate Julian’s Atlantic article above, or this one from London’s Gay Star News about a college-age playwright’s award-winning one man show about his search for sexual identity while struggling with porn addiction.) Shugerman then doubles down on the political angle by arguing that the whole campus wifi filtering movement is just a reboot of the religious right’s war on porn that cleverly coopts arguments from old-school feminists like Andrea Dworkin and Catherine MacKinnon. In constrast, she argues “today’s feminists” aren’t too fussed about porn. As to which, uh, are you sure about that? We’re pretty sure Melissa Farley and Gail Dines would beg to differ, as would Sara Ditum, a former critic of Dines’ who writes for the Guardian and other major publications. The problem we have with Shugerman casting the campus porn filtering debate in political terms is twofold. First, it’s just so lazy to pigeonhole porn skepticism into left/right, liberal/conservative tropes. As we mentioned, Shugerman wouldn’t need to search hard to find left-leaning speakers expressing alarm about porn use and abuse. Second, Shugerman herself reports that “[e]very student who spoke with The Daily Beast mentioned the levels of violence against women displayed in modern pornography” as a motivating concern. That doesn’t seem like an issue confined to one side of the political spectrum to us. At the very least, it would be nice to see the Daily Beast acknowledge the ambivalence men and women across the political landscape feel about how pervasive and influential porn has become in shaping modern sexuality. Part Four: Burying (What Should Have Been) The Lede But alas, that kind of complicated analysis doesn’t catch eyeballs. Instead, the Daily Beast article that opens by touting a movement by “college guys” to “ban porn on campus” concludes, ignominiously if you ask us, by giving short shrift to the most interesting issues buried in the campus wifi filtering debate. Would filtering be technologically feasible without restricting academic research? Would it have unintended negative consequences like deterring people who struggle with porn addiction from seeking help? Would it unduly restrict rights of free expression? It’s unfortunate Shugerman left these topics for the end of her piece, because they raise crucial questions inherent in any discussion of pornography today. So, there you have it, the basic anatomy of a lazy news article about porn: (1) grab attention with a false/reductive title and lede; (2) cherry-pick research to manufacture controversy; (3) POLITICS!; and (4) treat nuance like it’s for chumps. We haven’t tried it out on other articles yet, but we suspect it’ll hold. Which is too bad, because we all deserve better from our news sources when it comes to the public discussion of porn.

It’s an odd but distinctly American impulse to acknowledge the unhealthy effects of recreational screen use but to embrace constant interaction with screens as a fixture of the modern workplace. After all, one of our most ingrained cultural principles as Americans is that work can, and ideally should, be pleasurable and satisfying. For many of us, that equates to an expectation of feeling rewarded and fulfilled by a long day of typing out messages and staring at pixels.

Which leads us to wonder: is training ourselves to feel satisfaction from workplace screen interaction just as potentially unhealthy as seeking reward and stimulation through on-screen porn, games, or social media? At the very least, is it possible one activity reinforces the other, and vice-versa? Of course, few people achieve true fulfillment at work. Many of us find the hours we spend earning a living in front of a screen exhausting and mind-numbing. And yet, we go back to work, day-in, day-out, because we know we have to for our own economic survival, at the very least. We all have bills to pay. Working with screens is what most of us must do, and if we can find even a modicum of satisfaction in it, too, then we’ll count ourselves lucky. And so, at work we unconsciously train ourselves to find, if not necessarily happiness or stimulation, at least a sense of achievement and relief, from pressing “send” on an email, filling out an order screen, or scrolling through columns of numbers. Hitting a button or checking a box means we’ve completed a task. We’ve done what we needed to do to earn, maintain, and survive. Click click click, job done, mission accomplished, pressure from the boss temporarily relieved. Is it any wonder, then, that even in our off hours, we scroll, click, and text as if our lives depended on it? It’s not just that designers engineer porn, games, and social media to attract and hold our attention. Those features are effective, to be sure. But we suspect we also make ourselves susceptible to problematic use of porn, games, and social media by cultivating a relationship with screens at work in which we associate specific screen interactions like scrolling and clicking with accomplishing tasks and relieving stress. From personal experience, we can remember feeling like there was a feedback loop between at-work productivity and at-home porn use. The job functions we performed during the day, and the cycle of feeling and relieving tension by engaging in tasks on-screen, felt similar to (albeit somewhat less intense than) searching for and clicking on page after page of porn content. It was as if the previous night’s porn use was the proverbial shot, and the next days’s at-work screen time was the chaser. Screens aren’t going to disappear from the workplace. But, it may be possible to develop boundaries with our use of tech during the day that could translate into safer use at home. For some of us, that may entail adjusting our perspective of why we use a screen to begin with, and being mindful of only engaging with a screen for a well-defined purpose. Instead of falling in love with swinging a hammer, in other words, some of us may need to re-learn how to take satisfaction in having driven the nail.

Today is the second year anniversary of my father’s death. When it happened, I was a little more than a year into recovery from porn addiction.

My dad struggled with addiction throughout his life. When I left home for university, he gave me a talk about avoiding alcohol and gambling. “Those have been a problem for men in our family,” he said. He meant himself. I knew that and I heeded his warning. I drank in moderation (at least, for a college student). I never developed a taste for betting ponies or playing cards. I obeyed Nancy Reagan and just said “no.” But I have a compulsive side, just like my old man did. And when screens with porn on them came along, I got hooked hard. My dad hadn’t warned me about those. He hadn’t known to. They weren’t really a thing when I left home for the first time. When I entered recovery and started attending SAA meetings years later, my dad said he thought I was being too hard on myself. He was a product of his generation. He struggled with the notion of porn being harmful. Hell, he’d given me my first Playboy. I also don’t think he grasped how screens changed porn consumption, how they rewarded compulsivity and trapped people in a trance-like ludic loop, even as he played hours of hours of solitaire on the home computer (and maybe looked at porn, too, who knows). So, when I tried to talk to my dad about addiction, he mostly shied away. I wish he hadn’t, but as a dad myself I also empathize. I feel responsible for making sure my children won’t struggle with this disease. If they do, I’ll feel like I’ve failed them. And yet, my dad taught me profound lessons in confronting addiction that carry me through recovery every day. A great admirer of Winston Churchill, he often tried to foist some biography or collection of Churchill’s speeches on me to read. As sons are wont to do, I resisted with all my might. But, since my dad’s death, I have cracked those books and found, not surprisingly I guess, a wealth of experience, strength, and hope, as we say in the program. Churchill was a poet of overcoming adversity. I think that’s why my dad loved him. In October 1941, as bombs were still falling on London, Churchill visited his old prep school, Harrow, to deliver a speech to the student body which included this now-famous line: But for everyone, surely, what we have gone through in this period - I am addressing myself to the School - surely from this period of ten months this is the lesson: never give in, never give in, never, never, never, never - in nothing, great or small, large or petty - never give in except to convictions of honour and good sense. Never yield to force; never yield to the apparently overwhelming might of the enemy. My dad read that passage to me countless times as a kid. I shrugged it off back then, but no longer. Now that I see and know the threat porn addiction poses to my life and others’, I will never, never, never, never give in. I owe that resolve to one person. I miss you, Dad.

The cover story of the forthcoming issue of The Atlantic is a 14,000-word behemoth titled “Why Are Young People Having So Little Sex?” It’s worth your time to read, but if you don’t have the bandwidth, then not to worry. We can sum up the article’s (reluctant) answer for you in one word: porn.

Porn is the single most influential reason young people the world-over aren’t having sex. At least, that is the clear message author Kate Julian’s article sends. For readers of this blog, porn’s emerging influence over human sexuality won’t necessarily come as a surprise, but it seems to have frustrated Julian, who goes to impressive lengths (and length) to tease out a non-porn-related explanation for the world’s current “sex recession.” Yet, Julian’s insistence that the problem is not just porn, that it can’t really just be porn, only highlights porn’s obvious dominance. Of the five probable culprits she identifies in her investigation of the mysterious decline in young people having sex – masturbation, romantic immaturity, dating apps, bad (painful) sex, and inhibition – Julian cannot help but tie three directly to the influence of pornography. Her interview subjects report how masturbating to porn serves as “just enough” of a substitute for sexual intimacy to “placate [sexual] imperatives”, how porn sets a shame-inducing standard for what naked bodies and genitalia should look like, and how porn serves as a warped instruction manual for at-best unsatisfying, and at-worst injurious, sexual encounters. (Even Julian’s misguided doubts about the dangers of porn addiction and porn-induced erectile dysfunction find a quasi-foil in none other than Ian Kerner.) When the article doesn’t explicitly point the finger at porn, the ubiquity of screens as the sole medium of young people’s social interaction betrays porn’s behind-the-scenes influence. The same screens that Julian’s subjects use for watching porn also serve double-duty as a means of initiating sexual advances, and also avoiding them. Young men swipe right on Tinder in furious pursuit of an elusive sexual partner, while young women stare into their phones in purposeful avoidance of any perceived come-on from a real, live human. So pervasive is screens’ mediating influence in Julian’s telling that these young people find it quaint, but also unsettling and threatening, to interact with a potential romantic partner in person. What’s more, declining sexual intimacy among young people isn’t just an American phenomenon. Julian reports that countries in Europe and Asia have observed it in their young people too, despite distinct cultural differences among their populations. What could explain the common trend? Julian points to a correlation with the emergence of widespread broadband internet access in each country. In other words – say it with us – porn. Let’s pause here to acknowledge, as Julian does, that young people having less sex isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Abstinence among teens and early 20-somethings can prevent a host of social ills. Teen pregnancy goes down. Rates of sexually transmitted diseases drop. High school sweethearts make it home by curfew with their clothes on straight. And yet, as Julian points out, something is amiss. People around the world who are at the height of their sexual energy and fertility are avoiding sex on a population-level scale. Think about that. Think about the fact that forty-three percent of Japan’s population between 18 and 34 – 43%! – are virgins. Consider that, if Julian’s interview subjects are representative, young Americans find it “creepy” to say hello to someone to whom they’re attracted unless a screen mediates the interaction. Even after accounting for the benefits of a decline in teen moms and STDs, we’re still left with a dramatic shift in human behavior. And dramatic shifts, in our experience, presage chaos. Still, all is not lost. If the Atlantic’s article leaves you feeling concerned for the future of humanity, take heart in knowing that young people have begun to fight back against the tech and porn industries’ unregulated global experiment in manipulating their sexuality and social behavior. Over the past few weeks we’ve seen a steady stream of op-eds from university newspapers across the country rejecting the influence of porn, screens, and social media on the student-age generation. At Notre Dame, groups of men and women called for the university to filter porn from the campus wifi network, calling adult content an affront to human dignity and highly addictive. At Fairfield University, a student writer observed the “growing reliance on technology is an epidemic that deeply affects everyone with access to a phone.” The student newspaper at Colorado State called out social media for “making us … anti-social.” Since the beginning of the school year, similar articles have appeared in student newspapers at Mississippi State, and Pitt, and Southeastern Louisiana, among others. So, let’s not write the obituary of humankind just yet. Maybe the very same young people whose sexual behavior has departed so drastically from the norm will lead the way out of the virtual world and back into the real one, sex and all. |

AuthorLonger-form writing from the PornHelp team on current topics relating to problem porn use and recovery. Archives

June 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed